Penny: Designing a memory model to support a work stealing scheduler in the browser

Modern browsers give you workers but not threads, shared memory but not pointers, atomics but not fences, and message passing that copies everything. I wanted to see: Is it possible to build a real work-stealing scheduler — something like Cilk — inside these constraints? Penny is my attempt.

Why Bother building a scheduler

Because the browser’s concurrency model is fundamentally limited:

- No shared thread stacks

- No continuations

- No preemption

- Message-passing is expensive

- Workers cannot inspect each other’s memory

- SABs are powerful but extremely constrained

This makes it an interesting systems challenge:

Can we simulate a real work-stealing runtime inside an environment not designed for it?

Objective

The goal of Penny is to explore whether a work-stealing scheduler — similar to Cilk — can be implemented inside a browser, using only Web Workers, SharedArrayBuffers, and Atomics.

Initially I assumed the hard part would be implementing the Chase–Lev algorithm. In reality, the true difficulty was designing a memory model that fit the browser’s constraints.

This post documents the decisions, dead-ends, and constraints I discovered while designing Penny’s first memory model.

Environment Limitations

Penny is designed entirely within the constraints of browser execution:

- Message Passing is Expensive

postMessage copies non-SAB payloads. SAB + typed views must be used whenever possible.

- Strict Memory Alignment Rules

JS requires typed arrays to begin on specific byte boundaries. This constraint actually helps sab → L1/L2 cache locality.

- No Portable Thread Stacks

Workers have no accessible stack. No stack switching, no green threads. This is needed to avoid a single task monopolizing a thread.

- Functions Cannot Be Sent to Workers

Closures cannot cross thread boundaries. Workers must use a static function table.

These constraints influenced my decisions deeply with tradeoffs in mind

Memory Model - v0

The objective was to create a Chase-Lev deque to support work stealing.

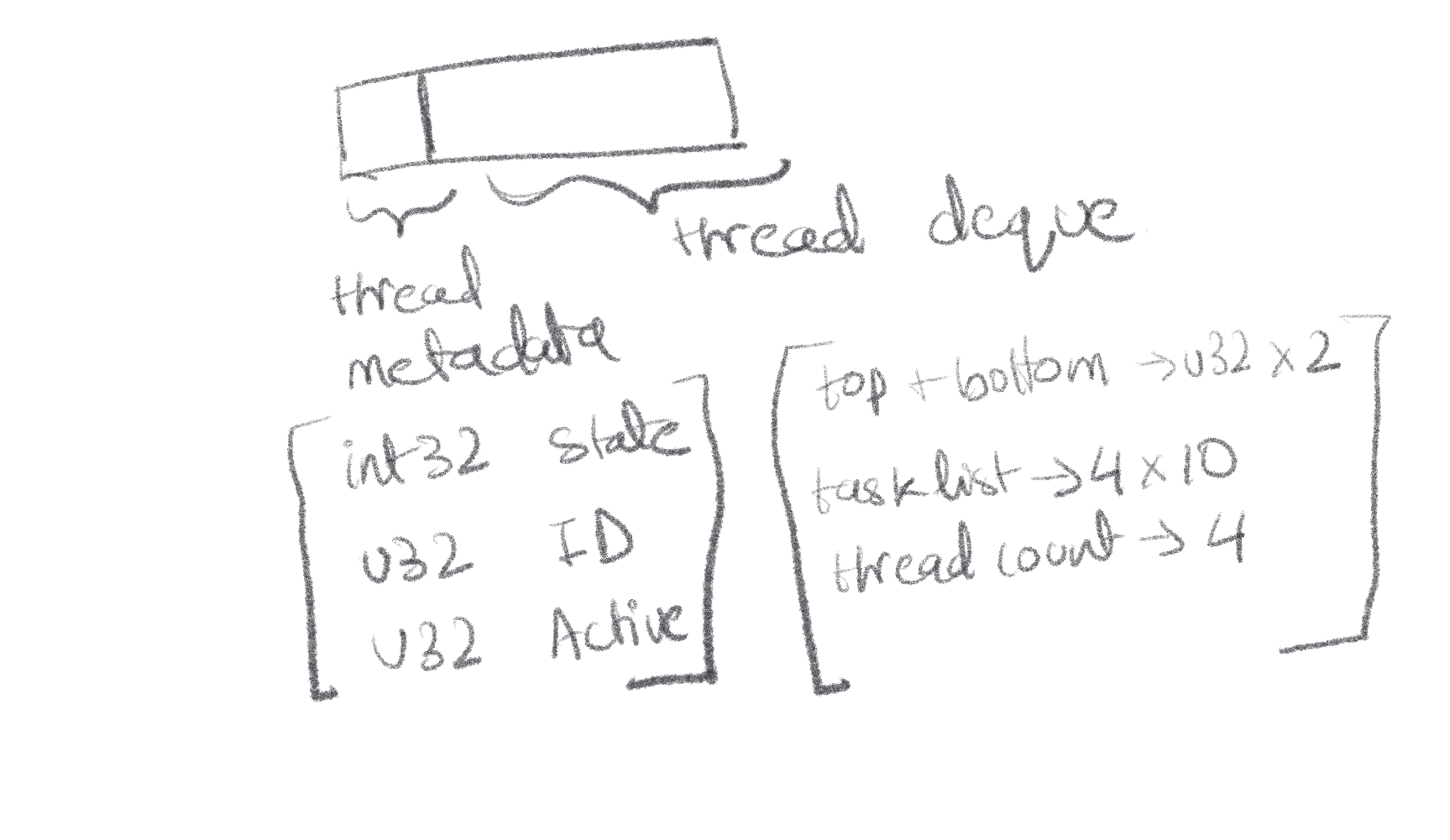

I added a basic sketch I used to reason about my first memory model for the scheduler. It looks a bit messy, but the idea behind it was that I would have a SharedArrayBuffer, deterministically determining the layout beforehand. And each thread would have it’s own view into it’s own slice of memory, essentially emulating the concept of thread memory (that can be easily, cheaply and quickly manipulated from either the main thread, or other threads from the pool). The key idea here was to use Shared Array Buffers (or SAB from here on), to reduce the overhead of message passing, and to give other threads to check tasklists of other threads, which is otherwise not possible in the browser

I added a basic sketch I used to reason about my first memory model for the scheduler. It looks a bit messy, but the idea behind it was that I would have a SharedArrayBuffer, deterministically determining the layout beforehand. And each thread would have it’s own view into it’s own slice of memory, essentially emulating the concept of thread memory (that can be easily, cheaply and quickly manipulated from either the main thread, or other threads from the pool). The key idea here was to use Shared Array Buffers (or SAB from here on), to reduce the overhead of message passing, and to give other threads to check tasklists of other threads, which is otherwise not possible in the browser

The basic layout of each thread’s memory slice would be:

- 4 bytes representing thread state. With 0 = sleeping, 1 = running & 2 = blocked by I/O

- 4 bytes representing the thread ID. Now, the scheduler will be responsible for handing out IDs, and it just a number from [0..n], with n being the number of threads. It’s important because the ID of the thread is what helps the thread index into the right window of memory, using

const baseOffset = threadId * THREAD_MEMORY_SIZE;

This was designed keeping in mind that SABs don’t let you create Views, if the memory address isn’t naturally aligned. Also, given the fact that atomics need INT32 array views, the state was set to that, so that we can use atomics to sleep or wake up threads, instead of busy waiting.

There’s a couple of issues here, such as:

- There’s only 4 bytes per top and bottom ptr. This would result in them being in the same cacheline. The bottom pointer is fine, since it should only be touched by the owning thread, but the top ptr would be constantly being touched by other threads, to steal tasks. This would lead to false sharing and tank performance quite a bit.

- The threads have their own deque, based on Chase-Lev deques which is great, but it’s a static array, that cannot be reallocated to a larger size. This would mean, that there would need to exist a global backbuffer to store tasks in case all threads have their task lists at capacity.

- There is no way for arguments for the task needed to be passed other than

postMessage(). This was mentioned earlier but this tanks performance heavily, and I wanted to avoid it from happening too much.

Scheduler design v0

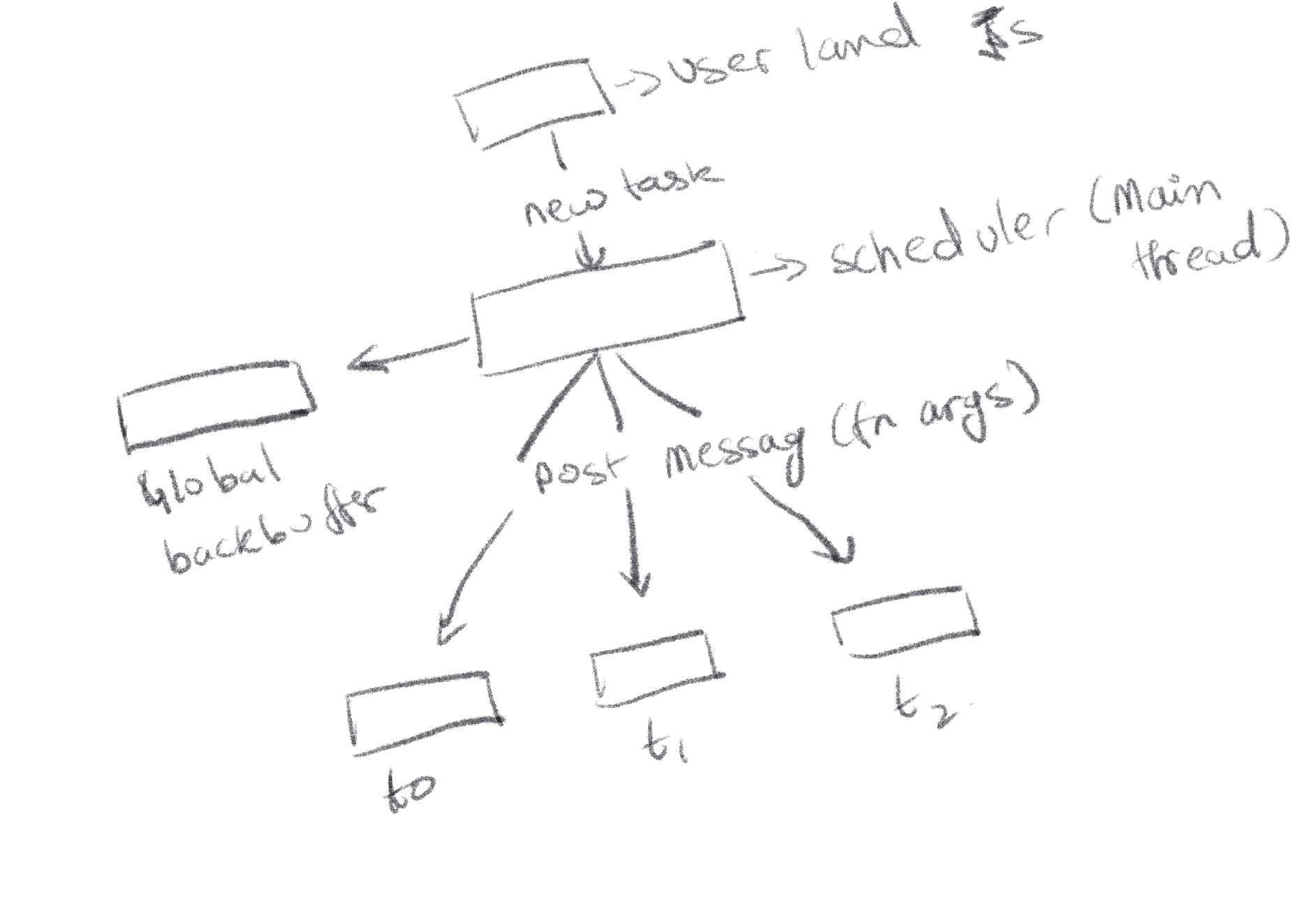

This was my first go at the scheduler design. The idea here was that, the scheduler would stay on the main thread. Initialze the thread pool and accept tasks from the user, to divy up between the threads.

There would also be a global backbuffer for excess tasks. The scheduler randomly picks a thread, and if it’s sleeping, tries to add the task to the taskList if it’s not at capacity.

const worker = this.threadPool[randThreadIndex].worker;

this.threadPool[randThreadIndex].state[0]= 1;

this.threadPool[randThreadIndex].tasklist[this.threadPool[randThreadIndex].bottom[0]] = taskId;

If at capacity, then push the taskId to the global backbuffer, which is another Ringbuffer.

The issue with this design is that:

- function args are copied everywhere

- task results are sent back by postMessage()

- To drain the global backbuffer, the scheduler needs to run in a loop or timeout on the main thread, which is highly likely to hitch rendering and other main thread ops.

Because of the above reasons, it was clear that this cannot be the right architecture for this. Hence I reworked the scheduler around these issues.

Scheduler design v1

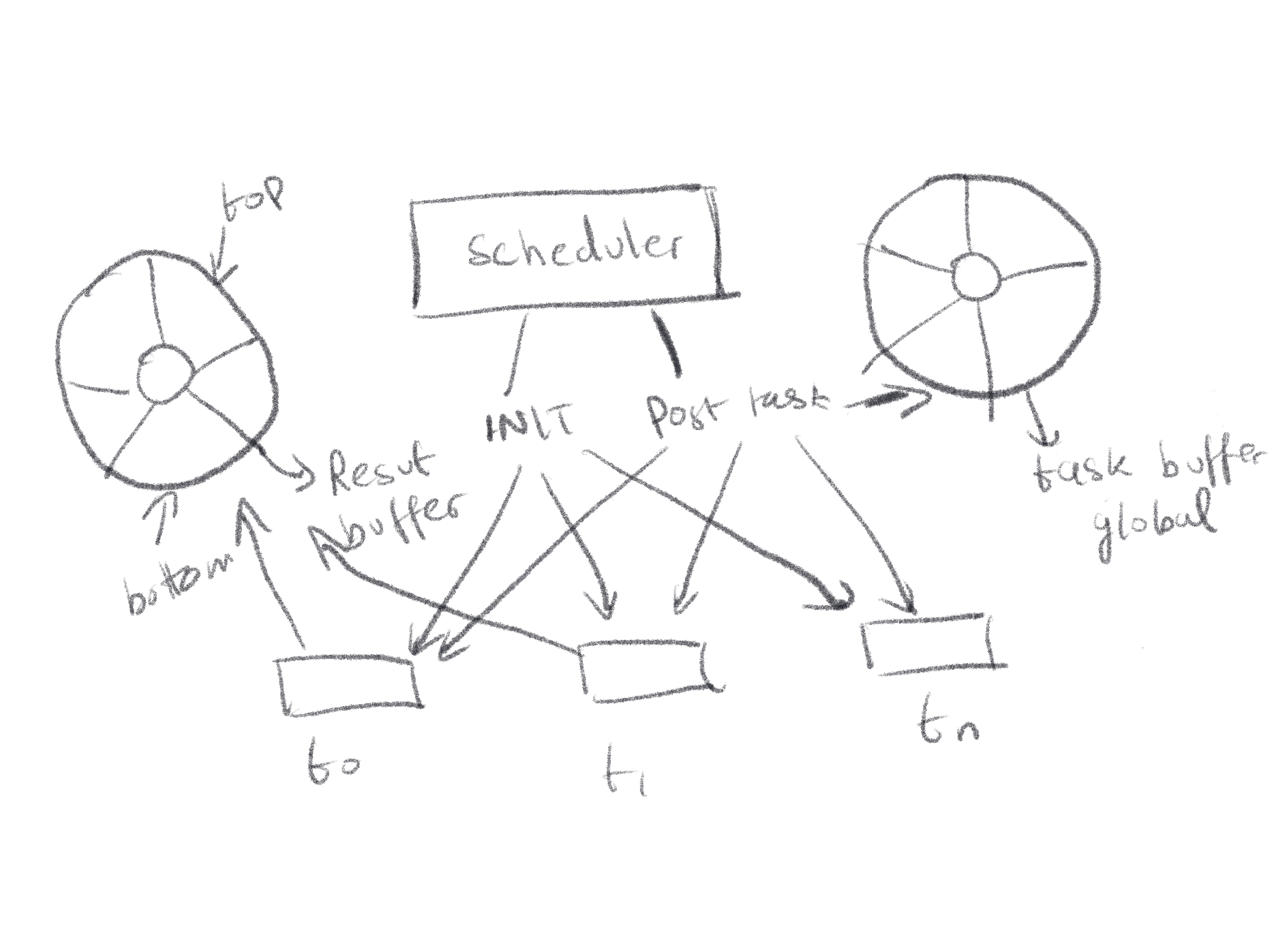

Forgive the fancy circles, they’re just the same as the thread deques (ringbuffers) that I got fancy with while sketching. The main difference being the global Task buffer would be LIFO (to support work stealing), and the result buffer would be FIFO.

This idea essentially treats the global task list as another worker thread, that the worker threads steal from if they can’t steal from anyone else. This makes sure that the main thread never gets stuck by the scheduler, all the scheduler does is just place the task into one of the available task lists.

Another improvement is that, threads write directly to the result taskbuffer lists, avoiding message passing and copying of results. This helps with not blocking the main thread (again).

The main concerns throughout all these designs have been making sure that race conditions don’t ruin task execution or thread behavior.

For the bottom pointers for the thread deques, it’s fine, since only the owning thread is able to manipulate them. but reading and manipulating top pointers, have to be done through Atomics, such as Atomics.load() , Atomics.store() and CAS operations to avoid ABA behavior.

Things to improve / explore

Right now JS execution is not very determinstic and if you notice in all the designs, it assumes that users will be passing and operating on basic data types. Almost all data passing through the boundary of the scheduler and user assumes that data will be of the few basic data types available. Also, given that all the values are being read as Int32/Uint32 there’s a significant chance of overflow, since JS numbers won’t adhere to that. Also, the lack of continuations points stops this from being a true fiber/green thread driven scheduling environment. A couple of options that I’m playing around with is, a small IR layer, where I inject yield() points into userCode based on cycles

Genuinely considering writing the core of the scheduler in WASM to get more deterministic performance, and exposure to features like stack switching Here

This is still under heavy exploration and I’ll most probably be changing the design soon, as I learn more.

For a more detailed breakdown, link to architecture_doc